This is my second reflection on cosmology and yoga. The first was Frank Answers About Yoga Harnessing the Wind and Releasing the Spirit. This one is about the yoga body connecting with Earth’s body. Just as I considered wind practice appropriate for late spring/early summer, so I consider earth practice appropriate for late summer/early autumn. I connected the wind practice with the liturgical festival of Pentecost. The earth practice would connect with fall harvest festivals.

An idea that I have been thinking about in recent years is that Earth is a living, breathing body. We humans are also living, breathing bodies. What does this suggest about the connection between our bodies and the body of the Earth? What does this connection suggest for our care of Earth and stewardship of its resources?

I had better explain what I mean by saying that the Earth is a living, breathing body. To say that it is a body is to say that it has a material composition and shape. To say that it is breathing is like saying that Earth is alive, just as our human bodies are alive if we are breathing.

Eco-philosopher David Abram writes in The Spell of the Sensuous (New York: Vintage Books, 1996),

As we reacquaint ourselves with our breathing bodies, then the perceived world itself begins to shift and transform. …organic entities—crows, squirrels, the trees and wild weeds that surround our house, humming insects, streambeds, clouds, and rainfall—all these begin to display a new vitality, each coaxing the breathing body into a unique dance. Even boulders and rocks seem to speak their own uncanny languages of gesture and shadow, inviting the body and its bones into silent communication.” (p. 63)

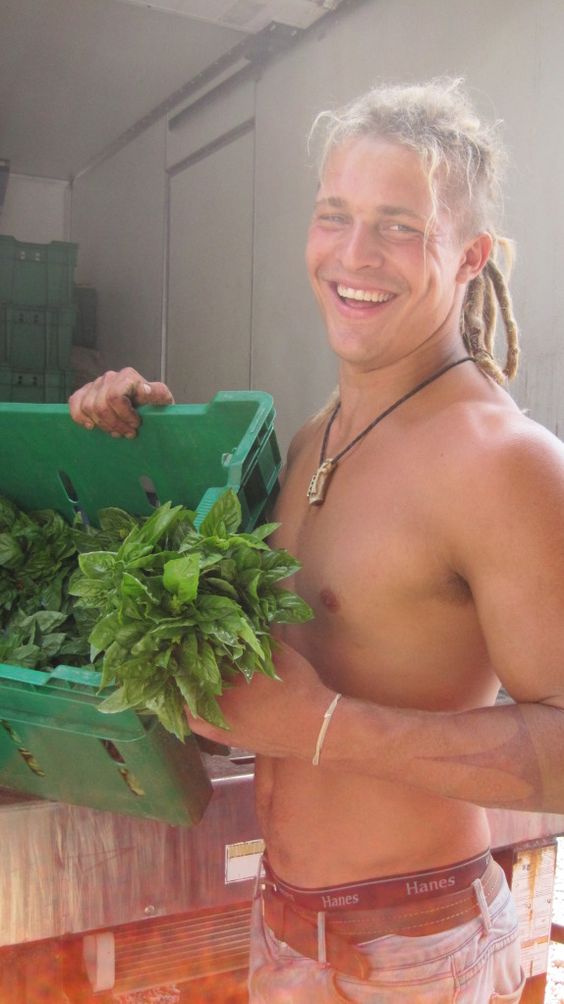

The fact is that Earth is teeming with life. It produces an abundance of food to nourish the animals and planets that live in its biosphere. But we live in the human world in which our economic, political, and social structures are predicated on scarcity rather than abundance. We believe there’s only so much of anything to go around. This attitude contributes to greed and hording by nations and individuals. This greed becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy because many people throughout the world are have-nots and live at the subsistence level. This is antithetical to the Biblical view of God’s bountiful creation and our commissioned stewardship to tend the garden of the Lord.

The universe itself is not static and limited. God has created an expanding universe. Within this universe we inhabit a planet that always has more than enough to give. Simply observe seeds, spermatozoa, and the life-giving cycles of sun and rain! At the onset of spring in the northern hemisphere we see the buds of renewed life springing forth from hibernation. At the end of summer we see that, as the psalmist says, earth has yielded its increase. Our problem is not insufficient resources to go around but economic, political, and social systems that don’t provide for sharing it’s production, and wars that interrupt getting food to where it is needed.

Food is the way we most directly and regularly connect with Earth, especially when the Fall harvest is gathered in.

Yoga has given attention to what we eat through its alliance with Indian ayurvedic medicine. Ayurveda divides the year into three seasons based on the predominant dosha associated with each. Since the traditional autumn season is divided between two doshas—early autumn is governed by the light Pitta diet, and late autumn and winter are governed by heavier Vata diet. Early fall is considered a transitional stage, occurring from mid-September to late October. During this time, it is important to feast on plenty of fresh, late-summer harvested fruits—namely fresh apples and pears. Fresh apples and pears are plentiful during this time, and they help to consume and “dry out” excess Pitta from the summer. These fruits also provide fiber, which helps move waste out of the gut, priming it to digest the heavier foods of winter.

Modern Cosmology

If ancient cosmologies saw the Earth as a living, breathing being, our modern cosmology thinks of Earth as an inanimate body—a ball of gases that spun off from a star, our sun, settled into its comfortable orbit around our sun, and cooled down. We speak of terra firma—the firm ground. But Earth is not as stable and solid we might think. It has a fiery center of molten rock that erupts through fissures in the Earth’s crust. We experience this as volcanic eruptions.

Earth’s crust floats on this hot molten interior and moves around as tectonic plates. We experience the collision of plates as earth quakes. Earth has a vast supply of surface water that, at least away from the polar regions, doesn’t freeze. Some of this water is absorbed into the atmosphere as clouds and we experience it as rain. The air we breath is not nothing; it is a gas. And the movements of Earth, combined with changes in atmospheric pressure and surface contours, cause a stirring of the air that we experience as wind.

These are the four elements that the ancient Greeks proposed in their cosmology and reflected on philosophically: earth, fire, water, and air. The ancient Indians added ether or space as a fifth element in their cosmology. Now we know that space is not an emptiness through which objects move, as Newton thought. Rather, it is the gravitational field, as Einstein proposed. And it is constantly expanding, as Edwin Hubble observed through his telescope.

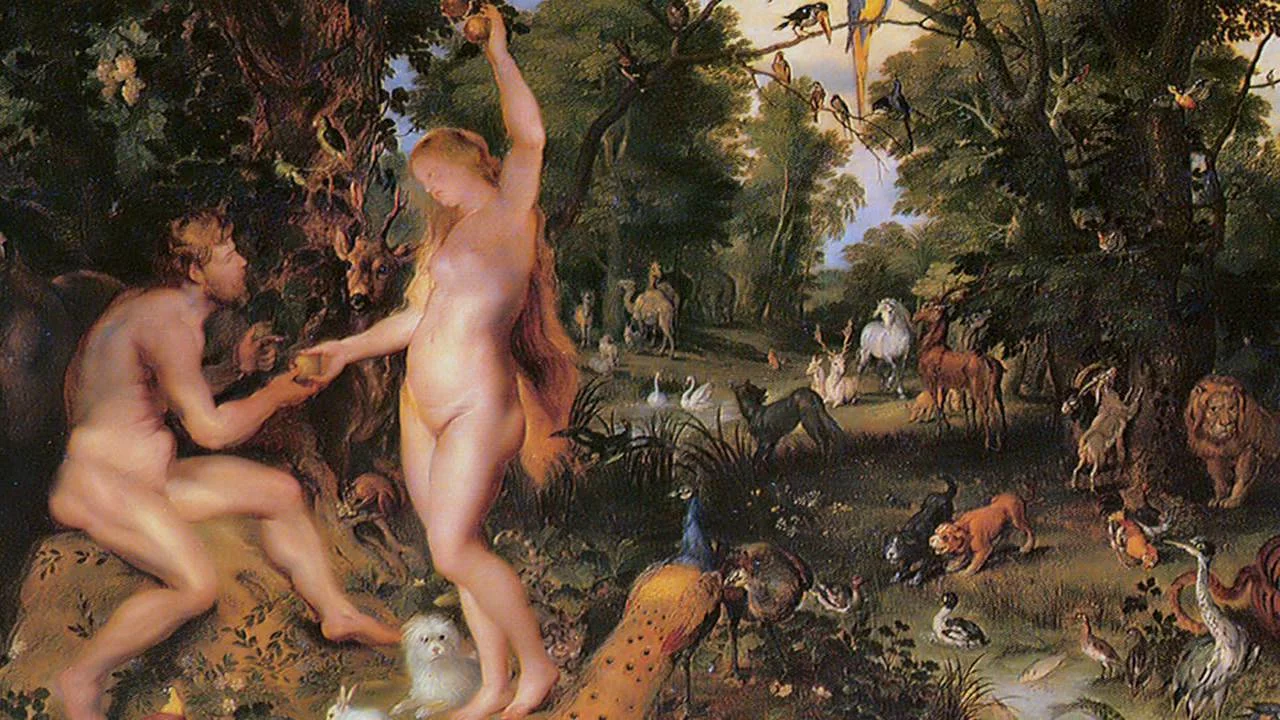

Theories of evolution have given us a different picture and a longer timetable for the emergence and development of life than the theological statements in Genesis 1 and 2. Roughly from single-cells to multi-celled plants and animals, from watery depths to swamps to land, from swimming and crawling to walking, life has sprung forth abundantly from Earth. Some of us would affirm that however it evolved the universe exists by the creative word of God and for God’s good pleasure. God pronounced this life-filled Earth as “very good.” At the apex of this creative process came humankind, created in the image of God (Genesis 1:24)—but created from Earth itself (Genesis 2:8). There is nothing in Earth, or in Earth’s star, our sun, that, materially speaking, is not in our bodies. Well do we call our planet “Mother Earth.” We are materially a part of it, and also a part of the plants and animals that are also of Earth.

One with All Plants and Animals

We humans, created by the mind and will and word of God, are of the same substance as Earth and all stars. But precisely because we are created in the image of God, we are each endowed with a soul (psyche, a unique personality) that our parent planet and grandparent star lack. Whether other sentient creatures have a soul is debatable. However, eco-philosopher David Abram, in Becoming Animals : an earthly cosmology (New York: Vintage Books, 2010), proposes that we share “mind” with other animals and perhaps even with Earth. He defines “mind” as awareness of ourselves and our surroundings. Traditional peoples also believed that plants as well as animals, and Earth itself, have awareness.

Abram coined the phrase “the more-than-human world” to describe everything that lives outside the human world. It speaks to a broader experience of Earth. Modern Western society is species-centric; we see humans as the center of life on Earth. We think of nature as inanimate except for animal forms. We lack awareness of the other life forms all around us. The concept of the more-than-human world invites us to open ourselves to the presence of all the other living things on this planet and to Earth itself as the mother of all life.

Gaia Theory

Ancient peoples lived in a closer relationship with Earth than do we modern Western and Westernized peoples. We made an erroneous theological presumption that subduing Earth and having dominion over it made it ours to exploit for our exclusively human purposes instead of managing it as stewards for God’s purposes . Science, too, took a detached approach toward the study of Earth that goes back to the Cartesian separation of mind from body. The primary dichotomy in Descartes’ philosophy was actually the division between the mind and the whole material world. That material world includes our bodies. Modern Western science detached us from Earth so that we could study it “objectively,” and detached our mind from our bodies. Our task now is to reconnect with Earth and sense how we are a part of it.

Gaia theory undoes these age-old presumptions. It holds that organic life is reciprocally entangled with the most inorganic parameters of earthly existence, thus complicating any facile distinction between living and non-living aspects of our world. It shows that Earth’s organisms collectively influence their environment so thoroughly that the planet’s oceans, soils, atmosphere, and surface geology together exhibit behavior more proper to a living physiology. We are all—plants, animals, humans, and Earth itself—part of a single biosphere. There is a reciprocal relationship between animals and plants. For example, we humans take in oxygen and give off carbon dioxide. Trees take in carbon dioxide and give off oxygen. So, yes, hug a tree.

See the May 2022 issue of National Geographic on “Saving Forests.” Heat and drought are killing our forests around the whole Earth.

Some of the beautiful, fun-loving people who come to The Bear Creek Music Festival braved the early morning chill to chill out with these buttressed cypress trees.

Christian Theology

Medieval Christians also had this sense of being connected with the whole creation. We know that St. Francis, in his Canticle of the Sun, called heavenly bodies like the sun and moon and other animals “brothers” and “sisters.” The great theologian Thomas Aquinas affirmed that God’s goodness is represented not only by humans but by all creatures. In his Summa Theologica I.47.1 he taught:

God brought things into being in order that God’s goodness might be communicated to creatures, and be represented by them; and because God’s goodness could not be adequately represented by one creature alone, God produced many and diverse creatures, that what was wanting to one in the representation of the divine goodness might be supplied by another. For goodness, which in God is simple and uniform, in creatures is manifold and divided.

In other words, we need the witness of all the creatures to know the goodness of God. Aquinas continues,

“The whole universe in its wholeness more perfectly shares in and represents the divine goodness than any one creature by itself.”

How could humans think we were the only or even the main event of creation? We are on Earth because God needed gardeners to tend God’s garden. If we have a “rational soul,” as Aquinas affirmed, it is so that we can communicate with our Creator about the work to be done in caring for Earth.

Experiencing Earth’s Body

I have come to think that the most important thing we can do is reconnect with Mother Earth as her loving children. Connection means to be in touch—literally! We need to be experiencing the Earth’s body in our own bodies. We need to get in touch with the Earth’s living, breathing body by getting in touch with our own living, breathing bodies. We need to shed the clothing of human culture and actually touch and be touched by Earth. We need to feel Earth under our feet by walking unshod on the bare ground, feel the breeze on our skins, breathe the fresh air into our lungs, notice the plants and trees, smell the foliage around us which tickles our nostrils, and hear the chirping of the birds and the rustle of the small mammals in the leaves that sends little vibrations into our ears. We need to connect with Earth.

As Simon Thakur, teacher of yoga, body movement, and meditation, says:

The current human disconnection from the natural world starts with our disconnection from our own bodies, which we as a culture inherited – to a degree that most of us generally don’t quite acknowledge the extent of our inability to feel our own bodies.”

Ancient yoga itself had a connection with the natural world that has been passed on to us at least in the names of the poses (asanas) (e.g. plants like lotus and tree, animals like cobra and dolphin). In his “Ancestral Movement” practices, Simon Thakur notes that humans humans were exploring physical movement in imitation of animals for survival long before recorded history and these movements are part of our collective embodied memory.

Indian Cosmology

With the change of seasons at the time of the autumnal equinox, we become more aware of the cosmos and its affect on us. Ancient Indian philosophy that has been embraced by yoga takes a more experiential approach to our apprehension of the cosmos than Western science. The word Samkhya literally means “to count” or “to enumerate.” It is a system that reckons with all the different things we encounter in our external and internal experiences. It differentiates between prakrti, energy that can be enumerated, and perusha, the seer or witness who experiences this energy and is conscious of it.

The basic building blocs of the Samkhya universe are the three gunas or “strands” that braid together the energies of prakrti (matter). These gunas are tamas (inertia, solidity, stability), rajas (activity, effort, motion), and sattva (balance, harmony, synthesis). These three strands have been associated with psychological states. The liability of this association is that we might think of one state as better or more beneficial to us that the others. But experience has shown that if we stay in one state too long we can become imbalanced. As yoga teacher Richard Freeman writes, “The yoga practices teach us to cultivate awareness in all of these different states of being so that we remain fluid, alert, and able to transition from one to the next skillfully” [The Mirror of Yoga: Awakening the Intelligence of Mind and Body (Boston and London: Shambhala, 2012), 82].

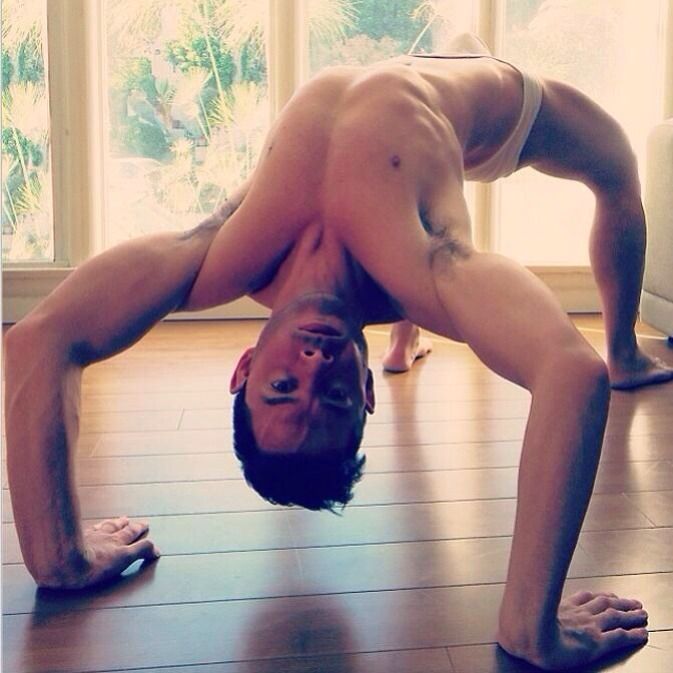

A Yoga Sequence: Tamas, Rajas, Sattva

In fact, skillfully constructed yoga sequences in asana practice lead us through the three gunas. We move from experiencing tamas on the ground in initial warm-up poses to experiencing rajas as we move up from our bellies to more vigorous standing poses to experiencing sattva as we return to the ground for a final synthesis and prepare for the final meditation. One way to look at this complete structure of practice is that each practice is an experience of the whole of life, from our emerging from Earth, to our striving in life, to our return to Earth from which we came.

Thus our practices often flow from initial stretches while seated on the ground to table pose with cat and cow stretches, to cobra, plank, and downward dog. This sequence often constitutes a repeated vinyasa or flow. These are tamas practices; they are warm-ups and they are grounding

Then we move up to lunges and standing poses. These poses are rajas practices; they require more effort. The standing poses such as lunges, mountain pose, chair pose, warrior poses, geometrical poses (e.g. triangle), balance poses, and twisting poses, reflect the activities of life.

For sattva practices we move back down to the ground, perhaps for some form of pigeon pose, which is a strenuous hip opener.

On the ground there is usually a final spinal twist

and then a symmetrical pose such as bridge, happy baby, or butterfly.

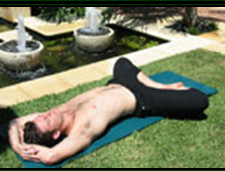

Savasana (corpse pose) integrates into our bodies and minds the whole practice while connecting with Earth that supports us and will finally receive us. It is said by yoga teachers that in corpse pose, as in death, there is nothing further to do. Death is often referred to as “rest.” Requiescat in pace. “Rest in peace.”

Corpse pose ends most yoga practices. It is a meditation in which the body and mind absorb what has transpired in the yoga practice. In autumn it is well to consider that we humans came from the earth and will return to the earth when we die. Many people are considering green burials in which the body is buried in a simple, biodegradable shroud or a casket made of wood or woven natural materials, which break down much more quickly and don’t release potentially harmful chemicals into the soil or water supply. Some even forego embalming, which hastens the decomposition process.

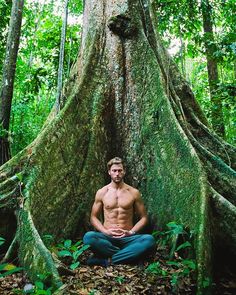

Finally, since yoga practice often ends with time for meditation, find a place in nature to relate to and sit in meditation regularly at that spot until you feel yourself becoming one with that bit of Earth or the tree under which you sit.

Pastor Frank