Question: It seems that liturgical dance is becoming more common in liturgies at church assemblies. Dancers are part of the procession or they enact Scripture readings. I feel that dance distracts from listening to the readings. Also, the congregation doesn’t participate in liturgical dance. They watch. This doesn’t seem consistent with the emphasis on active participation in the liturgy. Is there any tradition of the congregation dancing during the liturgy?

Frank answers: I have to admit that when I first experienced liturgical dance in the late 1960s I didn’t find it edifying. I suppose a couple of factors contributed to this. For one thing, I grew up in a German-American Lutheran church and we were rather stodgy when it came to body movement in worship. For another thing, I didn’t understand dance. I had not attended ballets, so I had no appreciation of what the dancers were doing with their bodies at the time.

I understood that in some cultures dancing was a part of rituals. I had participated in Native American dancing at Boy Scout summer camp Order of the Arrow initiation ceremonies. But I had no frame of reference for how dance could enrich worship like music could. German Lutherans were not into body movement, but they were into church music big time and I was a musician myself.

In my high school years and when I went away to college I began to discover how I could be more engaged in worship through my body in terms of gestures (e.g. making the sign of the cross) and postures (e.g. kneeling for confession of sins and intercessions). I came to realize through my experience that the use of gestures and movement put us in mind of what we are doing spiritually in worship. Years later I learned about embodied mind theory and came to understand that the way to the mind is through the body. What is dance other than the use of gestures and movement as heightened forms of expression to tell a story or convey feelings?

But just because something is obvious doesn’t mean we always immediately make connections. I’m happy to report that over the years I have seen a few ballets, like Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker and Stravinsky’s The Firebird as well as the dancing included in some operas and musical theater. So I have come to appreciate dancing as an art form.

My appreciation of dance grew after I started practicing yoga at the age of 65. As I was learning and doing the poses (asanas) and watched dance performances, I began to see similarities in the use of the body between yoga poses and dance movements. I have come to recognize the concentration of mind as well as the physical discipline that dance requires from my own efforts to do some of these poses. Yoga may even have taken some of its poses from ancient dance movements. One pose is actually called dancer pose or Lord of the Dance pose (Natarajasana).

Dancing in Indonesia

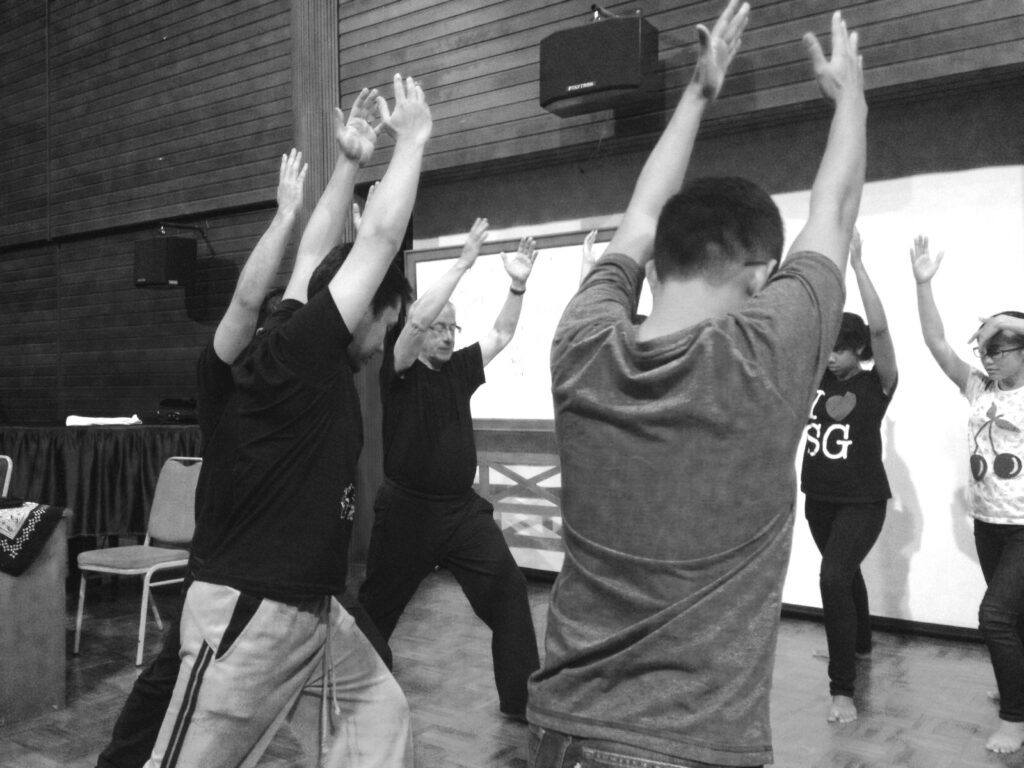

When I was invited to teach a course on liturgy in the Faculty of Performing Arts of Satya Wacana Christian University in Salatiga, Central Java, Indonesia in 2014, I knew I had to include lessons in the use of dance and plays in worship as well as music. Performing arts students communicate through their bodies in music, dance, and drama. The fruit of my studies is chapter 11 in my book Embodied Liturgy: Lessons in Christian Ritual (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014). This chapter, entitled “Bodies in Motion,” discussed dance and processions, liturgical drama and plays. We had a bit of dancing in a couple of class sessions: a welcome dance performed by a student in the department and a wedding dance/procession enacted by several students in the class to show the new couple making their way to their parents’ home to visit as husband and wife. When I introduced yoga sequences into the lectures to get the students into their bodies as we embodied some the realities Christian rituals deal with, I pointed out that it was just like choreographing a dance.

Rites of passage such as weddings and funerals are very elaborate in Indonesian cultures and dance is often involved. Indeed, dancing at wedding receptions is quite standard in American culture. Dancing at funerals isn’t. But the funeral rites among the Toraja people in South Sulawesi, Indonesia are very elaborate and dancing is included.

One of the highlights of my visit to Indonesia in 2014 was attending one night of the spectacular four night ballet enacting the Ramayana epic in Yogyakarta on the southern coast of Java. This experience really convinced me of the value of dance for pageantry and story telling.

Dancing in the Old Tetament and the Jewish Syangogue

When we look at Christian tradition, we don’t find much encouragement for dancing from the early church fathers. For them, dance was associated with pagan cults and erotic behavior at dinner parties. In spite of references in the Old Testament to dancing in the psalms and David’s ecstatic dance before the Ark as he brought it up to Jerusalem (2 Samuel 6:12-23), bishops discouraged dance as a part of worship (which might have taken place in a house church, inn, or cemetery, the kind of places in which erotic dancing might occur). Of course, the church fathers also discouraged the use of musical instruments because of their use in pagan cults and in accompanying dancing, in spite of references to their use in the Tabernacle and Temple in the Psalms and 2 Chronicles. The Eastern churches continued to prohibit the use of musical instruments in worship, but the Western church opened the door to their use once the organ was admitted.

Dancing has remained a part of Jewish life. At the celebration of Simchat Torah, when the annual reading of the Torah comes to an end, the entire congregation dances in a procession around the synagogue with the Torah scrolls.

History of dancing in church

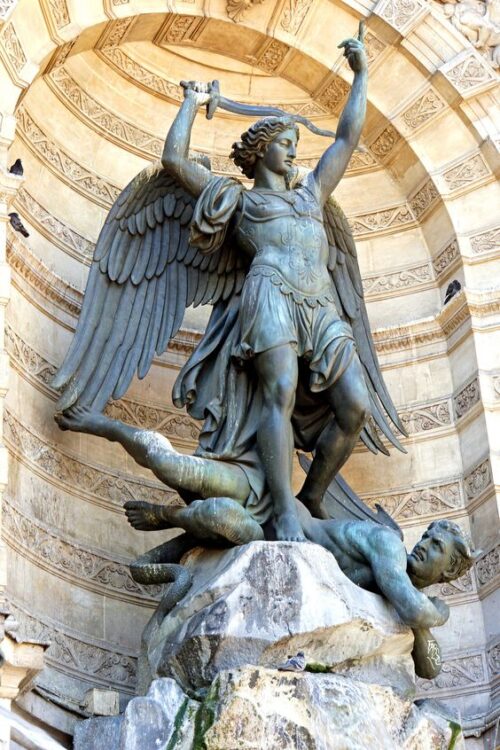

The fact that early Christian fathers discouraged dancing in places of assembly probably means that Christians actually were dancing. In the late fourth century, when Christian worship had been moved from more private venues into public halls called basilicas, John Chrysostom and Ambrose of Milan issued guidelines for proper forms of dancing in church. John extolled dancing on the feast days of martyrs and indicates that Christians danced throughout the city on those days. Ambrose even more positively said that dance should be regarded “as something which uplifts every living body instead of allowing them to rest motionless upon the ground or the slow feet to become numb…. The Lord bids us dance.” The kind of dance Christians practiced was most likely a round dance or circular dance that reflected the cosmic dance. Gregory of Nyssa even used the image of the cosmic dance to describe the dance of the Trinity with each other (perichoresis).

A dance step known as the tripudia — three steps forward, one step back — developed in the Middle Ages that could be used for round dances, line dances, and even in processions in which all could participate in. The most popular medieval dance form was called a “carol” or “carole” (French). These were round dances in which people held hands and faced toward the center with a kind of stopping and going movement. Carols were dances before they became songs. (Obviously people danced to a musical tune.) Dancing occurred on major festivals as expressions of celebration, such as Christmas and Easter, and on occasions of mourning and lament, such as the danse macabre.

Dancing and processing are similar movements. The people are going somewhere together. Processions have been an opportunity for dancing as well as walking. If we jump ahead to the 20th century we have the remarkable example of St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco that has built dancing into its liturgy and even had dancing saints painted on the walls of the church. The architecture provides for two worship spaces — one for the liturgy of the word in which the worshipers sit facing one another with an ambo for the readings in the middle; the other for the liturgy of the Eucharist in which worshipers stand around a table in the center under a dome. The worshipers dance their way from one room to the other using the tripuda steps while singing a hymn. A carol dance around the table concludes the celebration. I experienced this in the 1990s and found it very engaging. It was on the Feast of the Epiphany and I recall that the hymn lyrics we sang as we danced to the table were set to an early American tune.

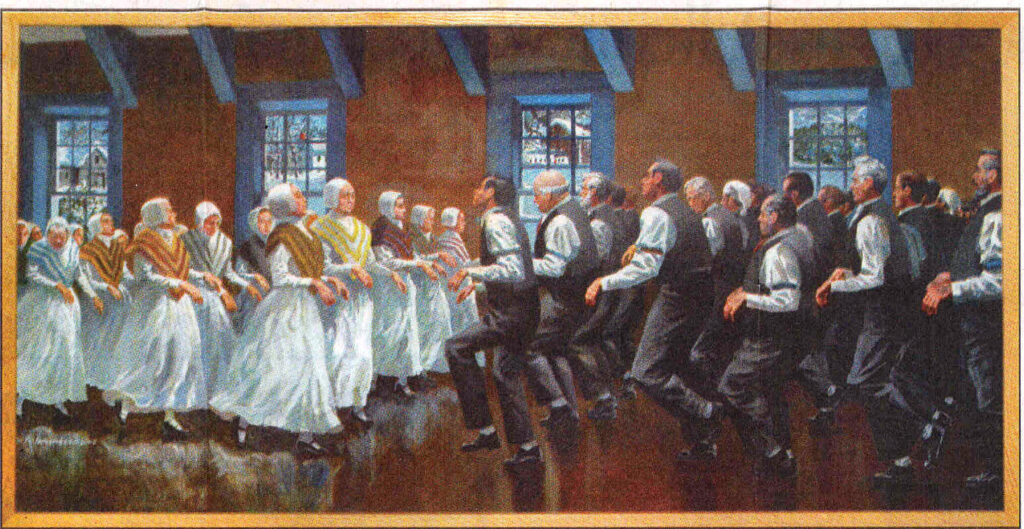

The most well known Christian group to employ dance as a part of worship was the Shakers, an offshoot of the Quakers who lived a simple life in a male/female celibate community in anticipation of the second coming of Christ. In addition to making beautiful but simple furniture they practiced a line dance with men on one side of the room and the women on the other.

I don’t think there are too many congregations that could incorporate structured dancing like these examples that involve the entire liturgical assembly. But if we think of processions as a form of liturgical movement, there are opportunities for Christians to put their bodies into motion in entrance processions on days like Palm Sunday and at the Easter Vigil and in gathering around the font for the renewal of baptism.

Our worshipers need to feel less physically inhibited in doing their Liturgy by, for example, extending the greeting of peace across the aisle, turning their bodies to face processions, and bowing to the cross as it passes. These are all gestures and postures worshipers can easily perform. African-American worship, Pentecostal worship, and contemporary worship have all modeled a freer use of the body to express devotion in worship. Orthodox worshipers also freely and unprompted move around the worship space to light candles, kiss icons, or line up to receive Holy Communion. But even if the whole congregation is not prepared to join in dancing, some members of the congregation can form a liturgical dance troupe just as some members form a rehearsed choir (both with competent direction).

Dancing in Africa and in African Churches

When it comes to liturgical dance, we must turn to African Christianity. In African cultures oral communication has predominated and orality is accompanied by hand gestures and body motions. The African theologian Elochukwu E. Ezukwu, in Worship as Body Language: Introduction to Christian Worship: An African Orientation (Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, A Pueblo Publication, 1997), proposes that in Africa oral communication and body movement are highly developed. Dance is a principal means of communication among Africans. “The dance,” he writes, “which involves an expansive, rhythmic, nonverbal movement of the body, is one key way of interaction in Africa. In the dance the body is most sharply displayed” (p. 6). Group dancing occurs for all occasions and it is part of liturgical inculturation in Africa to integrate dance into liturgy.

It’s not surprising that inculturation in the African churches found ways to include dancing, especially in the Roman Catholic Church which has been more open to inculturation than many Protestant churches.

Dancing occurs both outdoors and indoors in African churches. Worshipers will often join in swaying and clapping. It’s too bad the Western invention of church pews gets in the way of bodily movement.

Africans brought this body language to American even in their chains. Swaying with arms uplifted and clapping rhythmically is a common feature in African-American churches.

Dancing in worship

Pentecostal worship allows freer expression of the body than worship styles in other traditions. Pentecostal worship has not only promoted praise bands and praise choirs but now also praise dancers.

Did I say above that Germans could be stodgy in their use of the body in worship? German Catholics have recently been developing parish liturgical dance groups.

In view of all this, an answer to the question comes easily. Dance is practiced in just about all human societies and the liturgical churches have been open to the use of the arts in worship. Dance has had a long history in the church, both within the liturgy and alongside it. The use of the body to glorify God is well attested in Scripture. St. Paul even urges it in 1 Corinthians 6:19. Some church cultures are less comfortable with the use of the body in liturgical dance than others. Some individuals don’t think they can dance. Worshipers should not be forced into actions with which they are uncomfortable, but there is no reason congregations shouldn’t make dancing available as a way in which some people of different ages in the congregation can glorify God and edify the congregation. Dance is a way of putting your whole body into worship.

The history and living practices we have looked at suggest moments at which dance can be used in the liturgy. These would be primarily moments when there is movement in the liturgy, including the leading of processions – a ritual that naturally calls us to “journey” through a space. Such moments would include the gathering and entrance procession, the Gospel procession, the presentation of the Gifts, and the sending.

As for the use of dance during Scripture reading, I can see this occurring during the singing of the Psalm, but maybe not during the reading of the Lessons and Gospel. It’s not that we can’t watch and listen at the same time, but I would think the dancers need music (although I guess pantomime doesn’t need music). However, a dance interpretation of the text after its reading might invite a deeper internalization of the scripture we have heard proclaimed, just as there are musical responses to the Gospel (hymns, anthems, cantatas).

Ballet companies performing in church

In this connection I raise the question of whether ballet as an art form might be introduced in churches alongside the liturgy. Experiencing a biblical story being enacted in dance by professionals might be a way of showing people how the use of this art form can deepen our interpretation of texts, just like music and drama can. Churches have been patrons of the arts, including performance arts. This has been the case especially in music and drama. Congregations have hosted oratorios, passion plays, musicals such as Godspell and Jesus Christ Superstar (both of which include some dancing), operas such as Gian Carlo Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors, and I recently saw and heard a gripping performance of the cantata Considering Matthew Shepard by Craig Hella in the sanctuary of my home church. Are there ballets that enact gospel stories that could be performed in the sanctuary? This would be a way of extending appreciation of dance and also offering another way of presenting the biblical message.

One ballet I read about is entitled MC 14/22 (Ceci est mon corps) by the French choreographer Angelin Preljocaj. MC 14/22 stands for the verse in St. Mark’s Gospel, “This is my body.” The ballet requires 12 men (for the 12 apostles) and several tables. Not a word is spoken but biblically-informed viewers would see scenes from the fourteenth chapter of St. Mark that focus on the upper room, the last supper, the garden of Gethsemane, the skirmish at the arrest of Jesus, the confusion of the apostles, and conflicts between them. (Mark’s Gospel is not kind to the disciples.) Viewers might be led by the performance to ponder which “body” the dance portrays. Is it the sacramental body or the body of Jesus’ community or both? Could contemporary dance be performed in a church? I think some churches would be receptive to a work like this during Lent. Here’s a scene of the exhausted disciples sleeping in the garden while Jesus prays in the performance of MC 14/22 by the Scottish Ballet.

© Andy Ross.. Exhuasted on the table.

Dance can play a major role in inculcating an incarnational spirituality. Through a range of physical and emotional expressions, liturgical dancing can be a conduit of the Holy Spirit, reminding the assembly that God calls us to communion with himself through all of our senses and through all of the body’s motor actions.

Pastor Frank Senn

From my pastoral colleague in the Society of the Holy Trinity, Erma Wolf.

Frank, thank you for this thoughtful article. Most of all, thank you for your attitude of respect for dance as part of worship. I studied dance and did some work with dance in worship (liturgical dance), and am well aware that it can be distracting and self-indulgent, but at its best dance is as much a part of praise to the Lord as music and singing. If you are interested in seeing dance as an expression of religious experience, I recommend finding the Youtube videos of the Alvin Ailey Company’s “Revelations”, especially the segment “Wade in the Water.” It is exactly what you are writing about with the African-American church experience. (And if you’ve never seen it, find a copy of Martha Graham’s modern ballet, “Appalachian Spring.” The Preacher dancing his sermon is just remarkable! Plus the motifs in that ballet are some that I think you would find interesting.)

Trying to reintroduce dance into Western Christian worship is a daunting task. I appreciate your giving such good examples, and being supportive of those who try to do so. After all, if “every knee will bow” before the Lord, we will all have to move at least a little!