In your Frank Answers dealing with the practices of Lent you stress the practice of fasting. Fasting is a problem for many people today. We don’t receive much guidance from the churches on Lenten fasting and we’re often in social situations where meat is served even on Fridays. How can we observe the Lenten fast in today’s world?

Note: I am posting this article about fasting before Lent begins on Ash Wednesday because if we are going to be ready for fasting we have to think about it in advance.

Lent is a time of fasting. That’s what it is primarily about. It was originally a time when catechumens prepared for their baptism at the Easter Vigil by fasting and performing acts of ministry. It was not originally a time to remember the passion (suffering and death) of Jesus. That’s what Holy Week is for. This eludes us today because we no longer have a catechumenate and because fasting is no longer a regular part of Christian life.

Let’s be clear that fasting has been a normal part of Christian life since the first century. On Ash Wednesday we hear from the Gospel of Matthew Jesus’ teaching on the three notable duties of almsgiving, prayer, and fasting (Matthew 6:1-16). Jesus assumed that his disciples would keep the discipline of fasting. “Whenever you fast..”, not if you fast. The important thing in his teaching is that none of these disciplines, including fasting, give you spiritual bragging rights before God or before others. But the disciplines, including fasting, were presumed. That was the point of Jesus’ teaching, not that the “notable duties” should be abandoned by his disciples.

The church order known as the Didache (Teaching of the Twelve) at the end of the first century prescribed Wednesdays and Fridays as fast days (to distinguish Christians from the Jews who fasted on Mondays and Thursdays). Tertullian at the beginning of the third century explained the Friday fast as a participation in the passion of Christ. Wednesday became a weekly penitential day on which Psalm 51 was prayed. This remained a Christian practice in the Eastern and Western Churches down through the centuries. The Great Fast of Lent includes forty days of fasting, not including Sundays, because Sunday is the Lord’s Day, the day of resurrection. [On the origins of the Great Fast of Lent (Quadragesima or the Forty Days) see” Frank Answers About the Disciplines of Lent”.]

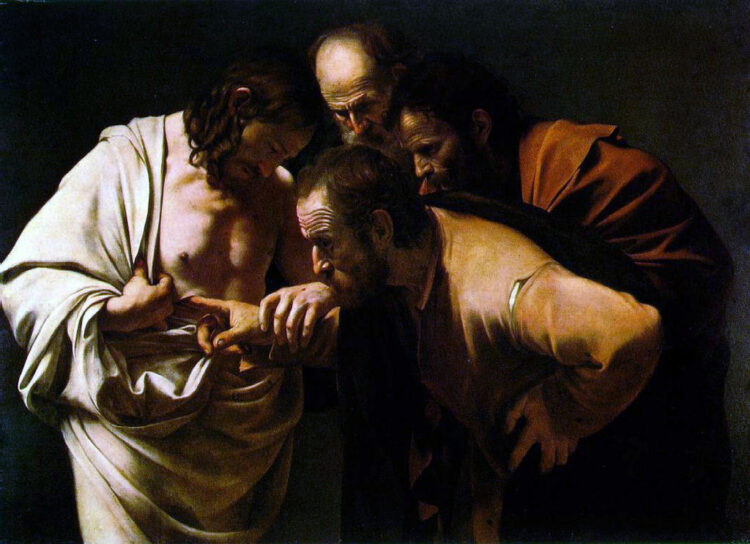

The Gospel for the First Sunday in Lent has historically been the temptations of Christ in the wilderness after his Baptism.

The first temptation in both Matthew 4 and Luke 4 is the temptation to turn stone into bread to satisfy his hunger. Adam and Eve were tempted by food — the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. As the serpent in the Garden of Eden tempted the first humans with food, so the devil tempted Jesus with food. The first temptation has been interpreted as a temptation of the Son of God to use his power to satisfy his own needs. Jesus responded by reminding the devil of the Torah’s teaching in Deuteronomy that “man does not live by bread alone.” But let’s not forget that the tempter was reminding Jesus of real needs for a real human body.

It’s true that fasting is a problem in our overstuffed society. The ancient church fathers and the Eastern Orthodox Churches to this day recommend and prescribe much fasting. But, as the question points out, modern Western people have great difficulty with fasting (as opposed to dieting). The great scholarly work of Peter Brown, The Body and Society: Men, Women, and Sexual Renunciation in Early Christianity (Columbia University Press, 1988; revised edition 2008) exposes our modern problem with fasting. Simply put: our modern Western bodies are not the same as the bodies of earlier times and other places in the world. Brown reminds us of the sharp discontinuities between our overly-fed modern Western bodies and the under-fed bodies of ordinary human beings in antiquity (as well as in some parts of the world today). In plain fact, some bodies are capable of thriving on less than we are, and often have to. In part, a cosmology or worldview is involved here that eludes us today. This is seen in the practices of the desert fathers and other ascetics in the ancient world. Let me quote from Peter Brown at length:

“There is no doubt as to the terrible privations that were involved even in the relatively stable life of the Pachomian monasteries. But we must remember that the body-image which the ascetics brought with them into the desert gave considerable cognitive and emotional support to their hope for change through self-mortification. It takes some effort of the modern imagination to recapture this aspect of the ascetic life. The ascetics of late antiquity tended to view the human body as an ‘autarkic’ system. In ideal conditions, it was thought capable of running on its own ‘heat’; it would need only enough nourishment to keep that heat alive. In its ‘natural’ state—a state with which the ascetics tended to identify with Adam and Eve—the body had acted like a finely tuned engine, capable of ‘idling’ indefinitely, It was only the twisted will of fallen men that had crammed the body with unnecessary food, thereby generating in it the dire surplus of energy that showed itself in physical appetite, in anger, and in the sexual urge. In reducing the intake to which he had become accustomed, the ascetic slowly remade his body. He tuned it into an exactly calibrated instrument. It’s drastic physical changes, after years of ascetic discipline, registered with satisfying precision the essential, preliminary stages of the long return of the human person, body and soul together, to an original, natural and uncorrupted state” (p. 223).

Fasting has been used in every spiritual system for the purposes of renewing the life force energy. When an individual chooses to fast for some period of time the benefits are tremendous. Fasting gives all the organs of digestion and assimilation the opportunity to heal and become more efficient. Fasting also leads to a shunting of energy away from the energy intensive process of digestion and towards the activation of our higher awareness centers/glands. This profound shift in energy can awaken latent gifts of perception and heightened states of awareness.

The ascetic, of course, engaged in permanent fasting and praying. The two go together in the history of spirituality. Setting aside time for prayer, worship, and/or meditation would be a complement to fasting. One might even meditate on the body and fasting. The best time for prayer or meditation is often in the morning upon arising and before getting into the affairs of the day. Prayer or meditation might provide you spiritual fortification for dealing with the affairs of the day.

The ordinary Christian had Wednesdays and Fridays and the Great Fast of Lent to keep the body tuned, as well as other fasting times throughout the year. But our ancient ancestors in the faith were starting from a better state than we are in recalibrating our bodies to “an original, natural…state,” one that the ancients thought would also foreshadow their resurrection bodies. Considering where we modern Westerners are starting from, a half-hearted fast on a few Lenten Fridays is not going to get us anywhere near this original or future state.

Our churches could do more to help us in recovering the physicality as well as the spirituality of fasting, including in what is served in Lenten suppers. In the last congregation I served before retiring, I asked a celebrated chef who is a member of the congregation to prepare a Lenten cook book with recipes for meatless or fish-based meals. Vegetarian cook books abound. Being a vegetarian, however, or even a vegan, does not relieve one of the discipline of fasting during Lent. Orthodox fasting during Great Lent preludes the food products that contain blood. The Orthodox Tradition is to fast from food products that contain blood. So, the Orthodox fast from meat, fish, dairy products, oil, and wine. ( Oil and wine, up until the last couple of centuries, were stored in animal skins. This rules should be revised for modern times This is why they can eat grapes and olives, but not have wine or olive oil. Shell fish can be eaten during Lent because they don’t have blood.)

I have come up with a half-measure fasting for myself. Fasting is the spiritual discipline of subjugating the flesh by depriving it of flesh—meat. That is the time-honored element to “give up” during Lent. (Meat was not an ordinary part of the ancient diet; it was served at feasts.) One could include all meat products in this fast, but I start just with the flesh. No meat on Fridays. If possible, make Wednesdays (the other traditional Christian fast day) also a meatless day. Then add no meat for breakfast and lunch during the whole of Lent: no bacon or sausage, no lunch meat. If your schedule requires ordering fast food, many places offer veggie burgers and tuna sandwiches. I’m even willing to give up my egg on the Wednesdays and Fridays of Lent, beginning on Ash Wednesday. This fast is doable. By the time we get to Holy Week you could fast daily in anticipation of the Easter feast. That would mean one main meal at the end of the liturgical day.

It is important to emphasize that fasting is not for the sake of dieting, detoxifying, or supporting world hunger. Those are good and noble purposes, but they can be done at any time. Nor is the Lenten fast just about self-denial. It is a penitential discipline of mortifying the flesh to prepare our bodies, that is, ourselves, for regeneration and resurrection.

I have developed a motto for the Lenten disciplines of fasting, prayer, and almsgiving that may be helpful: tone up, tune in, reach out. Fasting is an ascetic practice. “Ascetic” comes from the Greek word ascesis, which means “discipline,” such as athletes submit to when they are exercising to run a race. St. Paul used this term in 1 Corinthians 9:24-27 to compare the Christian life to running a race. The runner needs to tone up his body, tune into his mind, and reach out to the goal of the finish line.

Athletes are known for eating a lot, but they are also careful about what they eat. Certainly lots of protein from lean meat, fish. poultry, and eggs, but also fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and healthy fats. They leave high-sodium, high-sugar, heavily processed foods on store shelves. They follow a set diet, eating some things but fasting from others. So, too, in fasting we are submitting to a disciplined diet of eating some things, but not others. It’s not hard; it just requires ascesis – discipline. Athletes would also be able to give up meat by substituting other forms of protein.

As I wrote above, the traditional fast days for Christians were Wednesdays and Fridays. The Friday fast isn’t what it used to be even for Catholics. But many Christians, even Protestants, have become interested in practices of fasting as a spiritual discipline. The Roman Catholic Church today obligates its members to fast on Ash Wednesday, the Fridays in Lent, and Good Friday. The Good Friday fast might be carried over to Holy Saturday and end with the Break-fast after the Easter Vigil. Any or all of the forty days of Lent (that do not include Sundays, the Lord’s Day) may be fasting days.

The time of fasting has conventionally been from midnight to midnight because that’s easy to remember. However, the liturgical day is from Vespers to Vespers (sunset). This would mean that the Friday fast begins at Vespers (sunset) on Thursday and is actually over by Vespers on Friday. This could be convenient for those who have Friday night social events. However, I would encourage this practice only to get us attuned to liturgical practice, not to make it easier to fit into society.

There’s no question that a well-regulated fasting regimen can be good for one’s health in a society that tends to overeat. But also, over an extended period of time, fasting produces the mental clarity I wrote about above. This is the spiritual value of fasting. It explains why fasting and prayer or meditation go together. Fasting is generally done to purify and cleanse the body, but it is equally regenerative of the mind. The mind and body are not separate, they are fully and totally connected. A body filled with impurities will pollute the mind, and an imbalanced mind will naturally imbalance the body. Fasting brings body and mind together in an equilibrium. Only the regulation of the body and the calming of the mind makes meditation and prayer possible. A spiritual practical is not possible in a disembodied state.

It is clear that some guidance is needed for a people who are unaccustomed to fasting. Some proposals are to eat a big breakfast and smaller meals for lunch and supper, or to eat a big breakfast and one simple meal later in the afternoon. Getting in exercise before eating in the morning or afternoon is also recommended. Exercise burns calories and prepares the body to be refueled. I will be posting an article on “Lent and the Belly” which discusses abdominal exercises. The traditional Lenten fast, however, like the Islamic fast, recommends the big meal at the end of the fast day (usually around sundown or Vespers).

While the Lenten fast is a spiritual fast not undertaken for its potential health benefits, the stages of fasting are the same for any fast undertaken for any purpose.. At first you will feel hungry. This is when your body transitions into the fasting mode. For many people, it is the most challenging part of the fast. That may cause a reduction in your energy levels and make you irritable. It is wise to prepare yourself for this stage. Your body is going into a change of metabolism to prepare for a lesser amount of consumption. But once the body figures out the new normal, your energy will return and there are mental and physical benefits—if you stay with it. You will feel less hungry and more energetic. This is because your body starts to burn stored fat as its primary power source. It’s called the ketosis phase of the fast. There will be weight loss and a feeling of being healthier.

On the flip side, fasting causes a stress that provides an added benefit. This is a kind of mild stress that is comparable to the stress caused by exercise, which ultimately makes you stronger and your immune system more resilient.

People who have fasted have experienced a change in bowel movements and bad breath. There will be less bowel movement with less consumption. The big bowel movement will come when you break the fast (after Easter Day). Bad breathe is with us constantly but more frequent brushing is a good things.

Now, I hate to bring this up, but… Sexual abstinence has also been a part of the Lenten fast. For forty days? Well, Sunday is not a fast day. But there is a value in finding other ways of showing love and affection. There’s also also a value in men withholding ejaculation for a period of time (as Tantra also taught in India!). Spelling one’s seed depletes the body of energy. Abstinance would also be a good practice for unmarried couples. Sex after a time of abstinence is more enjoyable.

In any event, fasting has been an important aspect of Christian spirituality. In the liturgical calendar there are about as many fast days as feast days, which suggests moderation in the whole of life. From a biological perspective, fasting is about detoxifying the body, which can be assisted by practicing abdominal twists, especially if your last meal of the day has been big and rich. Keeping the body well regulated is also a spiritual practice.

Pastor Frank Senn

Supine spinal twist. Might be needed after Mardi gras.

Pingback: Frank Answers About the Disciplines of Lent - Frank Answers