Question: There’s a lot of violence in the world today. In recent months we have seen violence erupt in American cities in response to police brutality against black men. We see violence in other parts of the world, often because of sectarian strife. We see terrorist attacks all over the world. We have mass shootings in our own country. It seems that human beings have a propensity to resort to violence to settle differences. What does the Bible teach about violence? Is there a theological answer to violence?

Frank Answers: You are right. The daily news rubs the world’s violence in our faces: riots against police brutality in Ferguson, MO and in Baltimore, MD; children being gunned down in gang warfare in Chicago; the beheading of Christians and Western hostages by members of the Islamic State; home-grown terrorists and disaffected individuals going on shooting rampages and gunning down their fellow citizens in schools, churches, workplaces, night clubs, theaters, and places of public gatherings, as well as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Chamas and Israel. Violence also occurs in instances of domestic abuse, sexual harassment, unwanted aggression on the streets, and in many other instances.

The Bible is full of violence, beginning with Cain’s murder of his brother Abel. The exodus of Israel was accomplished by violence against the Egyptians—the death of all the firstborn of Egypt and the total destruction of Pharaoh’s army of chariots, charioteers, and horses. Some people lose their faith when they read the stories of the Holy Wars in the books of Joshua, Judges, and Samuel—wars in which the God of Israel is the general and no mercy is to be shown to the inhabitants of the land of Canaan, whose practices were an abomination to the Lord. The land that Christians call “holy” has been rife with violence since well before the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 and continues today.

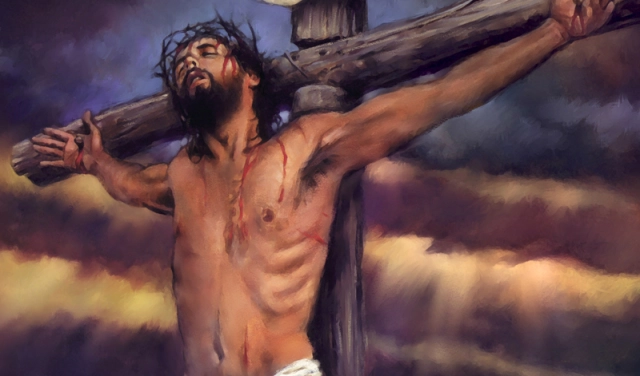

Christianity was born in violence—the passion of the Christ: stripped, whipped within an inch of his life, nailed to a cross and left hanging there in excruciating agony until he died from exhaustion.

The flogging or scourging of Jesus has been included as an article of faith in the Apostles Creed when we say that “He suffered under Pontius Pilate.” Flogging was a prelude to all Roman executions. If execution was by means of crucifixion the intensity of the scourging determined how long the victim would linger on the cross. In Mel Gibson’s film The Passion of the Christ, the flogging scene was especially gruesome. But it probably was in reality. Maybe that’s why Pontius Pilate thought he could placate the hostile crowd by having Jesus scourged. “Behold the man!” he told them. “Look at him.”

Judicial corporal punishment by caning or whipping is officially practiced in more than 30 countries in the world today. About a dozen countries, mostly Muslim, allow the flogging of women, although not on bare skin. The Romans were humane enough to exempt women from flogging…and from being crucified. But when shown the flogged Jesus, the crowd cried out for more. “Crucify him!” And Pilate eventually gave in.

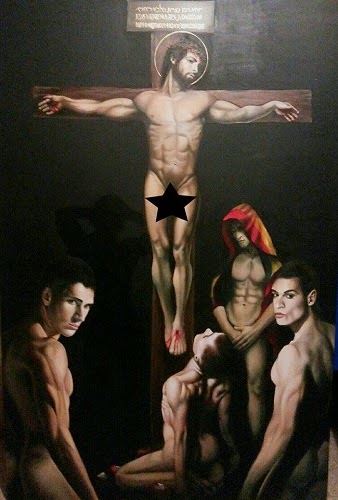

Christians came to regard the brutal execution of Jesus as a sacrifice of atonement. He was the scapegoat that was provided in the ritual of Yom Kippur (Leviticus 16). Two goats were involved in this ritual. One was slaughtered and offered to the Lord; the other was driven outside the Israelites’ camp to Azzel, bearing away their sins. This was the scapegoat. The mystery of who or what Azzel was suggests that this scapegoat ritual may have preceded the legislation of the sacrificial system in the Torah.

The reasons for violence are many and complex. They include nationalism and ethnic cleansing, oppression of minorities by majorities or by those in power, and the oppressed striking out against their oppressors, and sometimes sectarian rivalry. Sometimes persons or groups who feel they have been terribly wronged strike out at others. School shootings have been perpetrated by students or former students who were bullied or ostracized by other students. Probably the most infamous example in modern history has been the Nazi genocide against the Jews. The Jews were blamed for all the wrongs the Germans felt had been inflicted on them.

Scapegoating—lashing out at others—is a way human societies and individuals have dealt with their perceived wrongs, going all the way back to the beginning of the Bible. Abel’s sacrifice was pleasing to the Lord; for whatever reason Cain’s wasn’t. He took out his rejection by murdering his brother Abel. These acts of scapegoating becomes instances of evil, an infliction of harm and even death on others for the sake of doing it, and often justifying it on the basis of a twisted ideology or rationalization.

Cain’s murder of his brother Abel by Titian (1488/90-1576)

Violence through scapegoating is so endemic in human relationships that it was inevitable that someone would theorize about it. That someone was the French-born social philosopher Rene Girard. Girard’s theories of violence are complex but tightly argued. They can be reduced to these points:

- mimetic desire: all of our desires are an imitation of other people;

- mimetic rivalry: all conflict originates in mimetic desire;

- the scapegoat mechanism is the origin of sacrifice and the foundation of human culture, and religion was necessary in human evolution to control the violence that comes from mimetic rivalry.

- The Bible reveals the three previous ideas and denounces the scapegoat mechanism.

Reduced to utter simplicity, here’s how it works. Let’s say two children are playing. One of them reaches out to get a toy that neither of them had been playing with. The other child sees the first child reach out to get the toy and imitates him. He also now desires the toy. He reaches out to get the toy. If the first child insists that it’s “mine,” conflict erupts. They fight over the toy. Of course, the first child could have let go and the second child might have imitated that behavior too. We might call this the “turn the other cheek” method of avoiding violence. It can certainly be traced to the teaching of Jesus. It is the basis of non-violent responses to potentially violent situations, practiced by such people as Mahatma Gandhi in the campaign for Indian independence, Martin Luther King, Jr. in the American civil rights movement, and Nelson Mandela in the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa. Non-violent resistance has worked.

Another thing that can happen, however, is that potential rivals join forces against a third party, whose existence may have nothing to do with the problems experienced by the other parties. This is scapegoating. Rivals become allies, if not friends, by together scapegoating someone else.

But the sacrifice of Christ is proclaimed as a once-for-all sacrifice of atonement for the sins of the world. There is to be no other sacrifice of atonement to reconcile God and humanity and humanity and humanity with each other. Any further scapegoating is therefore anathema—rejected.

Scapegoating has led to violence against the Jews, against the Arabs, against African-Americans, against the police, against immigrants, against America and the West by Islamic terrorists, against Christians, and sometimes against one Christian group by other Christians (e.g. against Catholics by Protestants), and many others. The list is very long. And those who are scapegoated often strike back.

At the heart of the Christian faith are the deeply held convictions that the sacrifice of Christ alone is the basis of our justification and salvation, and therefore there cannot be any further atoning sacrifice, and therefore no other scapegoat is needed. The job of Christians in promoting peaceful coexistence between people of different races, ethnicities, and religions is to model non-violence in the hope that others will imitate it, as indeed the Hindu Mahatma Gandhi did in India against the (Christian) British Raj. (See the photo below of Gandhi leading the salt march in Indian in 1930 – a non-violent demonstration.) Gandhi said he learned non-violence from Jesus. So said also Martin Luther King, Jr. (who was also inspired by Gandhi) and Nelson Mandela (who was inspired by King). This strategy worked successfully in the Indian struggle for independence, in the American civil rights movement, and in the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa.

But sometimes police and military force is justified to protect defenseless people, for example, against gangs in our cities and against terrorist operations such as those of the the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State. It’s not a happy choice, because there are always negative consequences (as we have experienced with our American military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq). If local police are acting unjustly or with prejudice toward a group of people (the source of the “Black Lives Matter” movement), higher law enforcement agencies of the state or federal government must be called in to investigate and deal with civil rights violations. Government is also an order of creation (God’s left hand).

Police also have a responsibility for maintaining the peace. They used to be called “peace officers.” But God help us when we need to fight force with force.

This Holy Week we should consider those who are scapegoated in our society. They are often groups that can make a valuable contribution to our society, like LGBTQ people and immigrants and refugees. Jesus died to end all scapegoating. He is the once-for-all sacrifice of atonement. There is no need for another.

Pastor Frank Senn

Painting of crucifixion by Christopher Olwage.

Image above post: Crucifixion of Christ by Anton van Dyke